Frederic Church’s Art

Frederic Church used landscape painting to convey the expansionist, optimistic worldview of mid-19thcentury America. His panoramic canvases emphasize meticulous atmospheric and botanical detail. Viewers delighted in identifying specific species of plants and birds, the strata in rocks, and various cloud formations. Church wanted to use art to reconcile the latest revelations of the natural sciences and the age-old evidence of the divine in nature. Today, Church is acknowledged as a leader within the Hudson River School, often called the first truly American style of painting.

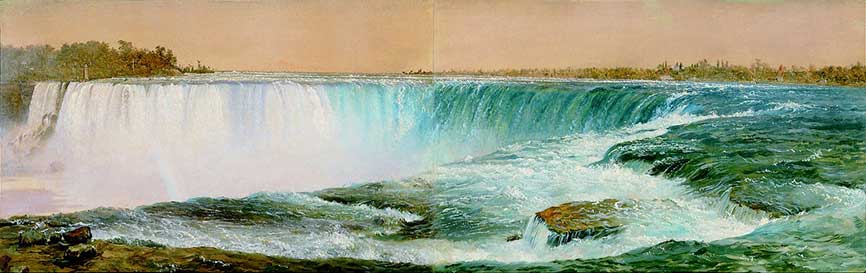

Church and the Hudson River School artists did not just depict views; instead, paintings were carefully arranged to celebrate the splendor of nature as a resource for spiritual renewal and an expression of national identity. In Church’s masterwork Niagara, 1857, he manipulated the falls, pushing down the near side to show the effects of water crashing on the far side and suspending the viewer in mid-air to intensify the grandeur of the falls.

Church was an artist-explorer. He traveled the world – the eastern United States, Colombia, Ecuador, Newfoundland, Labrador, Jamaica, and Mexico with pencil and oils, producing very accurate depictions of what he saw, working both en plein air and from memory shortly after returning indoors. His Heart of the Andes, 1859 is not a literal depiction of a location in Ecuador; for this work, Church artfully combined sketches from a variety of places – views of Chimborazo, drawings of a waterfall near Hacienda Chillo and palm trees and banana stalks sketched from Guayaquil. The finished painting is a summary of Ecuador. Each element is geologically or botanically accurate, but the painting shows the magnificent breath of topography and botany.

The Heart of the Andes is Church’s response to reading Cosmos the widely read work of the German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769 – 1859). Humboldt proposed that in the mountainous equatorial regions of South America, the unified workings of all terrestrial and celestial phenomena can be observed. Humboldt thought this akin to a glimpse of the Garden of Eden. Humboldt had explicitly called for a painter to visualize his ideas. Church rose to that challenge – and his final study for the Heart of the Andes is on view at Olana.

“Heart of the Andes” by Frederic Edwin Church, 1859, oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 119 ¼ inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Church’s first masterwork was “Niagara” (Corcoran Museum of Art) completed in 1857 when he was 31. Measuring over seven feet wide, the painting elevates the viewer above the great sweep of the falls known as the Horseshoe. With only water in the foreground and a rainbow at eye-level, the painting captures the majesty of the mighty waterfall and all its various effects of rushing water and tumbling mist. Niagara Falls had come to be a symbol for the wonders of new world and the new republic of America, and Church’s canvas was acclaimed abroad as the first great painting by an American artist. Church’s preparatory study for the painting hangs in the Sitting Room of Olana.

“Horseshoe Falls,” by Frederic Church, December 1856-Jan 1857, oil on two pieces of paper mounted on canvas, 11 ½ x 35 5/8 inches, Olana State Historic Site, OL.1981.15

Church achieved a major artistic and financial success with “Heart of the Andes” (1859, Metropolitan Museum of Art). He commandeered the exhibition room of the 10th Street Studio Building, then the center of the New York City art world, for a single canvas exhibition. The ten-foot wide painting was shown surrounded by palms, and was visible at night under gas light. Church charged 25 cents per person admission, and drew crowds. He sent the painting on a tour across America, and to London, and commissioned an engraving after it. The painting sold for $10,000, the highest price then ever paid to living American artist. The oil sketch for “Heart of the Andes” is still at Olana, as well as the steel engraving plate and numerous copies of the print. Other major paintings by Frederic Church include “The Andes of Ecuador” (1855, Reynolda House) “The Icebergs” (1861, Dallas Museum of Art) “Cotopaxi” (1862, Detroit Institute of Arts) “The Vale of St. Thomas, Jamaica” (1867, Wadsworth Atheneum) “The Parthenon” (1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art) “The River of Light” (1877, National Gallery of Art).

Frederic Edwin Church will forever be associated with the Hudson River Valley, where he painted and made his home; he is also known as a leading painter of the Hudson River School, often called the first truly American style of painting. Thomas Cole, Frederic Church’s teacher and mentor, is acknowledged as the progenitor of the Hudson River School. The school was not an academic institution but rather a loose association of painters who worked in a similar style. They were colleagues, friends, and supporters of each other, often traveling together in search of landscapes to sketch. They also exhibited together, especially at the National Academy of Design in New York City, and their paintings were issued as prints, so their images reached wide audiences throughout the rapidly-growing population of America.

“The Catskill Creek,” by Frederic Edwin Church, July-August, 1845, oil on beveled pine panel, 11 7/8 x 16 inches, Olana State Historic Site, OL.1980.1873

The Hudson River School flourished between the mid-1830s and the mid-1870s. Its subject matter is often landscapes from the Hudson River Valley, the Catskills, the Adirondacks, the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the coast of New England. An early canvas by Church that now hangs at Olana depicts Catskill Creek, a popular site for painters. As the country expanded to the West, the Hudson River School artists followed. Some painted Yosemite, Yellowstone, the plains of Nebraska, and other Western scenes. Others headed to South and Central America, painting lush tropical scenes. A number of Hudson River School painters traveled to Europe, the Middle East and even further afield. Paintings of the Hudson River School are characterized by fidelity to nature; clarity of detail; skies sometimes glowing at sunrise or sunset, sometimes shining a sunny, clear blue; nearly invisible brushstrokes; an overall feeling of tranquility. The Hudson River School canvases present the American landscape as a new Eden in a benevolent universe, blessed by God and providing an uplifting moral influence. The most prominent artists working in this genre include Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt, Asher Brown Durand, John Frederick Kensett, Jasper Cropsey, Thomas Worthington Whittredge and Sanford Robinson Gifford. The popularity of the Hudson River School landscapes began to fade by the 1870s. More introverted, poetic styles of landscape painting came to fore, including Tonalism and eventually American Impressionism; these styles emphasized looser brushwork, higher color and evocative, allusive subject matter. By the early twentieth century, earlier landscapes appeared bombastic and hopelessly dated. The term “Hudson River School” originated, in fact, as a disparaging label applied to the old-fashioned style of painting. It was only in the 1960s and 1970s that paintings by Church, Bierstadt, Gifford and their contemporaries began to be admired again, and the term Hudson River School was used as praise. Today Hudson River School paintings command respect all over the world.

Frederic Church had strong ties to many of the Hudson River School artists. First and foremost was Church’s teacher and mentor, Thomas Cole. From Cole, Church learned how use landscape to embody historical and religious themes. Later, Church employed Cole’ son Theodore (“Theddy”) to manage his farm, and maintained close ties with Cole’s widow and the rest of his family at Cedar Grove. A comparison between the two artists can be made in the East Parlor of the main house, where “Autumn” by Church, an 1856 painting showing the brilliant foliage of the season, hangs beside “Solitary Lake in New Hampshire by Cole, an 1830 painting showing a lone Indian, rifle in hand, pausing on the shore of a wilderness lake. Many years after Cole’s death, Church purchased and hung Cole’s canvas depicting the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

“View of the Protestant Burying Ground, Rome” by Thomas Cole, probably 1833-4, Olana State Historic Site, OL.1981.17

Sanford Robbinson Gifford was raised in nearby Hudson, New York, but he probably first met Frederic Church in New York City, where both were young aspiring landscape painters in the 1850s. The two became friends and traveled together, including trips to Mount Khatahdin in Maine and a camp that Church established there. Gifford is probably the painter of Olana’s canvas depicting the camp with its rustic lean-to structures and view of Lake Millinocket and Mount Katahdin. Gifford is known for large canvases of wilderness scenery suffused with soft, glowing, golden light. Jervis McEntee, a native of Roundout, New York, became student of Church in the winter of 1850-1, and the two remained lifelong friends. McEntee and his wife Gertrude were often visitors at Olana, and McEntee and Church both kept studios in the 10th Street Studio Building. Jervis McEntee accompanied Frederic Church to Mexico once. McEntee’s paintings often depict quiet, late autumn or winter scenes and are often distinctly melancholic in tone. Frederic Church retained a long friendship with Martin Johnson Heade, whose inclusion in the Hudson River School is a matter of scholarly debate, since Heade painted relatively few landscape paintings. For a time, the two shared a studio in the 10th Street Studio Building. Heade traveled to Brazil and Jamaica, and painted the birds and flowers he found there. One of Heade’s orchid paintings still hangs at Olana.